[This is a poem by Amiri Baraka. A dear high school friend of mine, Sarah Liebman, showed it to me years and years ago, and it has always stuck with me. It is one of those pieces of art that says beautifully something I have never wanted to say, and part of my fascination with it has had to do with realizing that I have never wanted to say this, and still don’t, but that it is so simply and honestly put that I want to listen. Or maybe it is more accurate to say that I have wanted to say some of this, but not all; and I haven’t wanted to come to rest in the places this poem comes to rest.]

Lately, I’ve become accustomed to the way

The ground opens up and envelopes me

Each time I go out to walk the dog.

Or the broad edged silly music the wind

Makes when I run for a bus…

Things have come to that.

And now, each night I count the stars.

And each night I get the same number.

And when they will not come to be counted,

I count the holes they leave.

Nobody sings anymore.

And then last night I tiptoed up

To my daughter’s room and heard her

Talking to someone, and when I opened

The door, there was no one there…

Only she on her knees, peeking into

Her own clasped hands

[Thanks to Russell Johnson, who found it on phdstress.tumblr.com]

“And if anyone complains that prunes, even when mitigated by custard, are an uncharitable vegetable (fruit they are not), stringy as a miser’s heart and exuding a fluid such as might run in misers’ veins who have denied themselves wine and warmth for eighty years and yet not given to the poor, he should reflect that there are people whose charity embraces even the prune.”

[“A Room of One’s Own”]

“SUPPOSE, for the sake of argument, that a man were turned into a mackerel. His sentiments touching the change may not be a matter for urgent, but they cannot fail to be a matter for clarifying consideration. There are many things that he would lose by passing into the fishy state; such as the pleasure of being in the neighborhood of a Free Library, the pleasure of climbing the Alps, the pleasure of taking snuff, the pleasure of joining a heroic political minority, and also, I suppose and hope, the pleasure of having mackerel for breakfast. But there is one pleasure which the man made mackerel would, I think, lose more completely and finally than any of these pleasures: I allude to the pleasure of sea-bathing. To dip his head in cold water would not be something sacred and startling; it would not be to have all stars in his eyes and all song in his ears. For the sea-creature knows nothing of the sea, just as the earth-creature knows nothing of the earth. This forgetfulness of what we have is the real Fall of Man and the Fall of All Things. The evil which infects the immense goodness of existence does not embody itself in the fact that men are weary of woes and oppressions. It embodies itself in the shameful fact that they are often weary of joys and weary of generosities. Poetry, the highest form of literature, has here its immortal function; it is engaged continually in a desperate and divine battle against things being taken for granted. A fierce sense of the value of things lies at the heart, not merely of optimistic literature, but of much of the best literature which is called pessimistic. Assuredly it lies at the heart of tragedy; for if lives were not valuable tragedies would not be tragic. If life begins by taking things for granted, poetry answers by taking things away. It may be that this is indeed the whole meaning of death; that heaven, knowing how we tire of our toys, forces us to hold this life on a frail and romantic tenure.”

[G.K. Chesterton, from an article reprinted in “The Living Age”, volume 244 (January, February, March 1905). With thanks to Karl Johnson who sent this passage to me.]

[Dorianne Laux]

this morning begins almost purely, coffee

enveloped in cream, those clouds that bloom up

like madness in a cup, and i take the first swallow

before the color changes, taste the bitterness

and the faint sweet behind it, steam

rubbing my nose, an animal nuzzle,

and the sharp, nearly painful heat

at the back of my tongue, the liquid

unraveling down the raw tunnel of my throat.

and i feel my body fully, vessel of desire,

my stomach a pond of want and warmth,

utterly human, divine and awake. and i can hear

each bird’s separate song, the chirt and scree,

the sip, sip, sip, the dwindle and uplift yearning,

the soup’s on, soup’s on, let up, let it go

of each individual voice, and i know i am here,

in this widening light, as we all are, with them,

even the most damaged among us or lonely

or nearly dead, and that for each of us there is

some small sound like an unseen bird or

a red bike grinding along the gravel path

that could wake us, and take us home.

this morning i think I’m prepared for

the final diminishment, with something

like a waking, ready awe. my complaints

folded and put away in a drawer

like needlework, unfinished, intricate

woven roads that go nowhere or disappear

in the distance, rough wanderings

that have brought me here, to this

sleep-repaired morning, these singing trees

and into my own listening body.

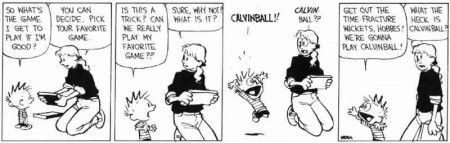

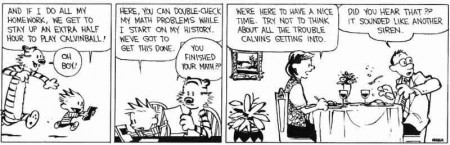

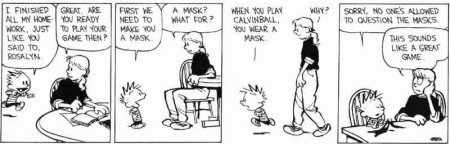

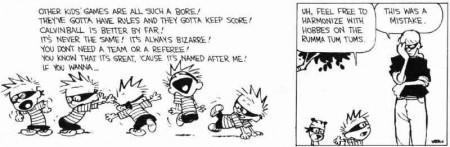

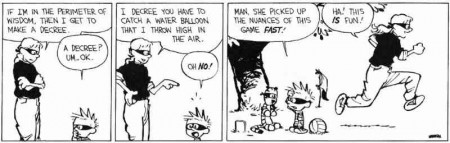

This is what life feels like right now: the speed, the terror, and the fun. I am working on a name of my own; Stephanieball is not quite it. Tangoball is closer.