“For truth… those dots mark the spot where, in search of truth, I missed the turning up to Fernham.”

[This is a review I wrote for Books & Culture; it was in their June/July issue and is online here.]

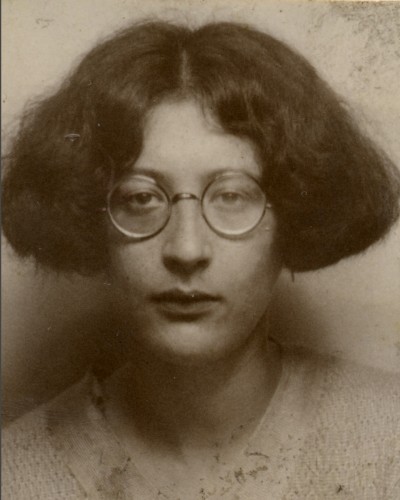

I first “met” Simone Weil on the cover of Gravity and Grace. Above the title (which was in pencil-thin red letters), there was her name in heavy black, and above that, against a pure ivory backdrop, a nearly abstract face given form by its shadows, stamped in black—the lips, a bit of shadow under the nose, the lashes and one lower lid, the solid irises each with one spot of light, the outline of the round horn glasses. No chin, no eyebrows; no edges to the face, exactly, and the black splotches on the side might conceivably be hair, or they might not.

“Two ways of renouncing material possessions,” she wrote:

To give them up with a view to some spiritual advantage.

To conceive of them and feel them as conducive to spiritual well-being (for example, hunger, fatigue, and humiliation cloud the mind and hinder meditation) and yet to renounce them.

Only the second kind of renunciation means nakedness of spirit.

Weil abstracted herself nearly out of existence while she was alive (the black-and-white cover image is true to her in this, and her notebook entries, as above, avoid “I” whenever possible). Given this abstractness, it is striking that she should so often produce a powerfully personal response in those who encounter her words. “She scares me shitless,” Stanley Hauerwas has said. “That ferocious intelligence coupled with her self-destructive tendencies.” She asks such deep and honest questions; she is compelling. And yet she cannot simply be followed, and so she is terrifying.

Weil was overcome on the one hand by the unspeakable suffering that fills the world, and on the other hand by encounters with the love and the absence of God—and the God she had in mind is the one described by Catholicism. Those of us whose moral imagination has been captured by the young Parisian Jewish woman come to her words and the story of her life asking many different kinds of questions. Filmmaker Julia Haslett comes asking, “How am I to live in a world with such depth of suffering?” More specifically, Haslett wants to know, “How do I live compassionately in such a world without committing suicide? And why?” This is not an academic question; debilitating depression runs in Haslett’s family. Her father killed himself when she was in her teens, and one strand in her film, An Encounter with Simone Weil, is a conversation with her older brother, also struggling with suicidal depression.

The film is the story of an extravagant quest, a life-or-death search for Simone Weil. It is Weil’s line, “Attention is the rarest form of generosity,” that first rivets Haslett. Somehow, she feels, if she can only come to terms with Weil, she will find answers to her questions. She spares no effort: in Paris archives, she watches hours upon hours of film from Communist Party meetings and protests at which Weil (though not a card-carrying member, because the party was insufficiently radical) might have been present. She visits Weil’s first cousin Raymonde Weil; her student Jeanne Duchamp; and Florence de Lussy, who is compiling Weil’s Oeuvres Complètes in many massive volumes. Haslett interviews her own brother, Timothy, as well as Anna Brown, an activist and political science professor who has been deeply shaped by Weil’s life and ideas. She interviews Weil’s niece, Sylvie Weil, who has recently written her own book about her aunt, and is said to look just like her. Sylvie speaks of growing up in her aunt’s shadow, feeling deeply torn between her own personality, which was nothing like her aunt’s, and the towering figure her father (Weil’s brother André, an eminent mathematician) so deeply admired. “Really, I wanted to be Brigitte Bardot,” she says, laughing.

Still, after all her interviews and reading and archival hunts, Haslett is unable to feel Weil “answering back.” As a last expedient, she places an ad in New York City for a francophone actress whose job it will be to attempt to embody Weil. She hires Soraya Broukhim, and has her read Weil’s writing and take a job briefly in a factory (as Weil did for a year, in spite of her crushing migraines, abnormally small hands, and the physical clumsiness that led to burns and other injuries). Then Haslett interviews Broukhim, who sits across the table chain-smoking just as Weil would have done. Even this fails to get Haslett any closer to Weil than the mute photographs did.

I felt decidedly furthest from Weil in the scenes with Brouhkim; even Sylvie Weil’s non-Simone character (or Weil’s cousin Raymonde, in her one-sentence appearance, bristling with dislike for Simone) felt closer to the woman Haslett was seeking. As the camera cut from Haslett, asking the questions, to Broukhim, it was not the actress’s face but Haslett’s own, elegant and marked by grief and weariness, that resembled the Simone Weil whom I know through photographs and words. Cigarette and curly black hair notwithstanding, Broukhim looked far too undamaged to be Weil. Weil barely consented to inhabit her own body; why would she be findable in an actress’s face? This woman does not know the answers to your questions, I wanted to say to the screen. You know them much better yourself. My disappointment was heightened by a wordless shot of Broukhim, wearing eyeliner (which Weil is reported to have done only once in her life, in order to get hired at the Renault factory) and wrinkling her forehead to simulate the pain of a migraine.

One other scene with Broukhim strikingly embodies both the film’s seriousness and the ways in which its quest founders. Throughout the film, Haslett reads powerful, resonant sentences from Weil’s work; the film would be worth watching just for these lovingly chosen lines, which are convincing evidence that Haslett began her quest by reading everything Weil wrote. (It would also be worth watching for any of the many interviews, in which Haslett has clearly won her interviewees’ trust and honesty.) But back to the scene: Near the end of the film, over a beautiful shot of a bare, stone-walled room with sunlight slanting in, Haslett reads, “Two prisoners whose cells adjoin communicate with each other by knocking on the wall. The wall is the thing which separates them but is also their means of communication. It is the same with us and God. Every separation is a link.” This I found moving, especially given Haslett’s avowed difficulty in identifying with the spiritual dimension in Weil’s thought and life. But there is another shot set in the same space, of Broukhim silently leaning her forehead against the wall. That this second shot felt so deeply wrong, so far from Weil, had in part to do with the sense of hearing Weil that I had had in the previous scene.

Given Haslett’s family’s struggle with suicide, I see how Weil has failed Haslett in providing reasons to stay alive, and it seems entirely right for Haslett (and others) to reject Weil as a role model even while valuing her thought. There is a sense, however, that Haslett’s questions finally limit what she is able to see of Weil’s life and death. The conclusion that Weil was self-destructive and died of self-starvation is accurate but incomplete. The English coroner wrote in 1943 that “the deceased did slay and kill herself by refusing to eat when the balance of her mind was disturbed.” Yes, and interpretations of Weil’s death as an act of pure heroic spiritual asceticism are incomplete; but it seems to me that her final months are best understood as a continuation of the deep conflicts she wrestled with throughout her life. She found it conceptually impossible to love the particular, and yet she was helplessly in love with the specific beauties of this world—and with the people of her native land. Her death of tuberculosis and starvation at age 34 was really caused, so one biographer has written, by a broken heart over occupied France.

The strength of the film is in Haslett’s honesty, her refusal to pretend to have found answers she hasn’t found. Her courage is deeply moving. My disappointment at the failure of her quest finally to encounter a Simone Weil who can answer her questions is a function of the film’s capacity to get me to commit to its central arc. Haslett had me asking her questions with her; I wouldn’t have been disappointed if the film had not at first convinced me that against all odds, she was going to find Simone Weil.

But Weil is elusive; her writings are largely fragmentary, and almost all were published posthumously. Even people who knew her when she was alive struggled to get her into focus, to see her as more than a collision of black and white shapes. And like many of these people, Haslett is thrown off-balance by the bluntly spiritual questions that motivate Weil’s thought. The film’s ending suits its subject. Weil was herself a fierce seeker much more than a source of answers.

The NY Times recently posted this article by Paul Elie, who wrote a book I love called The Life You Save May Be Your Own, which is a quadruple biography of four twentieth-century American Catholic writers (Flannery O’Connor, Dorothy Day, Thomas Merton, and Walker Percy). I thought what he said was intelligent and thought-provoking, and I’m curious what other people think. In fact, I’ve come up with questions, and if you have thoughts I would love to hear them (you can comment below and maybe there will be an *actual conversation* on my blog; or if you’d rather, you can e-mail me from the “About” page.

Here are my questions:

1. Are there fiction writers Elie doesn’t mention who you think are writing successfully from the perspective of believers or faithful people (Christian or otherwise)? For Christian ones, I thought of Ron Hansen, Linda McCullough Moore, and Brett Lott. Also Susan Howatch in some of her books.

2. He doesn’t say lots about this, but he seems to imply that there’s better writing from the perspective of people in other faith traditions. Chaim Potok comes to mind for Jews, for example, so in a sense I think he’s right. Why is this? Is Christianity like whiteness, the one ‘race’ that is invisible and has no history and no defining characteristics? That can’t be it, can it?

3. One of my courses last semester was about religion and modernity, and one of the things we discussed early in the semester was that (especially if you’re talking about something like Hinduism), the term “belief” is not ideal for describing what is most important about religion or faith tradition. What do you think? What is “belief” good for, and what are its limitations as a concept or a word? Are there better words that get at more of the core of what living faithfully is about?

4. Do you care whether fiction loses its faith? If you’ve read this far, my guess is you do — but whether you do or not, why?

“It is a curious fact that novelists have a way of making us believe that luncheon parties are invariably memorable for something very witty that was said, or for something very wise that was done. But they seldom spare a word for what was eaten. It is part of the novelist’s convention not to mention soup and salmon and ducklings, as if soup and salmon and ducklings were of no importance whatsoever, as if nobody ever smoked a cigar or drank a glass of wine. Here, however, I shall take the liberty to defy that convention and tell you that the lunch on this occasion began with soles, sunk in a deep dish, over which the college cook had spread a counterpane of the whitest cream, save that it was branded here and there with brown spots like the spots on the flanks of a doe. After that came the partridges, but if this suggests a couple of bald, brown birds on a plate you are mistaken. The partridges, many and various, came with all their retinue of sauces and salads, the sharp and the sweet, each in its order; their potatoes, thin as coins but not so hard; their sprouts, foliated as rosebuds but more succulent. And no sooner had the roast and its retinue been done with than the silent serving-man, the Beadle himself perhaps in a milder manifestation, set before us, wreathed in napkins, a confection which rose all sugar from the waves. To call it pudding and so relate it to rice and tapioca would be an insult. Meanwhile the wineglasses had flushed yellow and flushed crimson; had been emptied; had been filled. And thus by degrees was lit, half-way down the spine, which is the seat of the soul, not that hard little electric light which we call brilliance, as it pops in and out upon our lips, but the more profound, subtle, and subterranean glow which is the rich yellow flame of rational intercourse. No need to hurry. No need to sparkle. No need to be anybody but oneself. We are all going to heaven and Vandyck is of the company—in other words, how good life seemed, how sweet its rewards, how trivial this grudge or that grievance, how admirable friendship and the society of one’s kind, as, lighting a good cigarette, one sank among the cushions in the window-seat.”

[Virginia Woolf, from A Room of One’s Own, on which I am currently trying to finish a paper. This seemed a lovely passage for a feast day. A few pages later is the famous comment, “One Cannot think well, love well, sleep well, if one has not dined well. The lamp in the spine does not light on beef and prunes.” While I was typing this, I was also struck that it is a counterpoint to the prevalent myth that good creative or intellectual work is primarily done by people who are in extreme, and possibly self-destructive, agonies. I think it is part of the great good news in the world that suffering can in fact feed powerful art and powerful thought. But it is heresy against that same good news to act as though only cheap or shallow art comes out of delight, or pleasure, or gratitude.]

My father [to my mother]: I was just trying to get a rise out of you. [Pause.] My dad loved that expression, ‘Get a rise.’ That’s what he’d always say, “I was just trying to get a rise out of your mother.”

My mother: No, that was just his lame-ass excuse for why he made her mad all the time.

My father: That is exactly the right word. It’s an immaculate word. [Pause.] That was another of his favorite expressions, ‘immaculate.’ Strangest thing. He barely used adjectives at all otherwise. He’d always say, “This restaurant is immaculate.”

Me: By which he meant it was clean?

My father: No. That was the thing. That’s not what he meant at all.

You can see their breath in the air. And at just around three minutes, you can hear them calling.

“We have read your manuscript with boundless delight, and if we were to publish your paper, it would be impossible for us to publish any work of a lower standard. And, as it is unthinkable that in the next thousand years we shall see its equal, we are, to our regret, compelled to return your divine composition and beg you a thousand times to overlook our short sight and timidity.”

[Not my rejection, alas; it was sent to a friend of Brian Doyle’s, who wrote about it here.]

[This is a favorite passage of mine from Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. I feel inclined to defend haymaking and tomato-growing, but other than that, re-reading this to post it earned me the comment from my housemate, “You’re smiling lovingly at your computer screen.”]

Thomas Merton wrote, “There is always a temptation to diddle around in the contemplative life, making itsy-bitsy statues.”

There is always an enormous temptation in all of life to diddle around making itsy-bitsy friends and meals and journeys for itsy-bitsy years on end.

It is so self-conscious, so apparently moral, simply to step aside from the gaps where the creeks and winds pour down, saying, I never merited this grace, quite rightly, and then to sulk along the rest of your days on the edge of rage.

I won’t have it.

The world is wilder than that in all directions, more dangerous and bitter, more extravagant and bright.

We are making hay when we should be making whoopee; we are raising tomatoes when we should be raising Cain, or Lazarus.

Ezekiel excoriates false prophets as those who have “not gone up into the gaps.”

The gaps are the thing. The gaps are the spirit’s one home, the altitudes and latitudes so dazzlingly spare and clean that the spirit can discover itself for the first time like a once-blind man unbound.

The gaps are the clefts in the rock where you cower to see the back parts of God; they are the fissures between mountains and cells the wind lances through, the icy narrowing fiords splitting the cliffs of mystery.

Go up into the gaps. If you can find them; they shift and vanish too.

Stalk the gaps. Squeak into a gap in the soil, turn, and unlock—-more than a maple-—a universe. This is how you spend the afternoon, and tomorrow morning, and tomorrow afternoon. Spend the afternoon. You can’t take it with you.